Researchers have dispelled narratives about the Pompeians victim’s casts by looking into ancient DNA

Scientists believe long-standing assumptions about the people of Pompeii may be false after analyzing ancient DNA samples.

On October 24, 79 AD Mount Vesuvius erupted. Considered one of the deadliest volcanic ejections in history, the event saw several Roman settlements being buried under mammoth pyroclastic surges and ashfall deposits.

Arguably, the most famous of these Italian towns was Pompeii, where the unprecedented eruption tragically killed around 2,000 residents in the city’s vicinity.

A 2021 study revealed that inhabitants had ‘no escape’ and that those who managed to survive the initial phase of the eruption eventually lost their lives to dangerous pyroclastic flows.

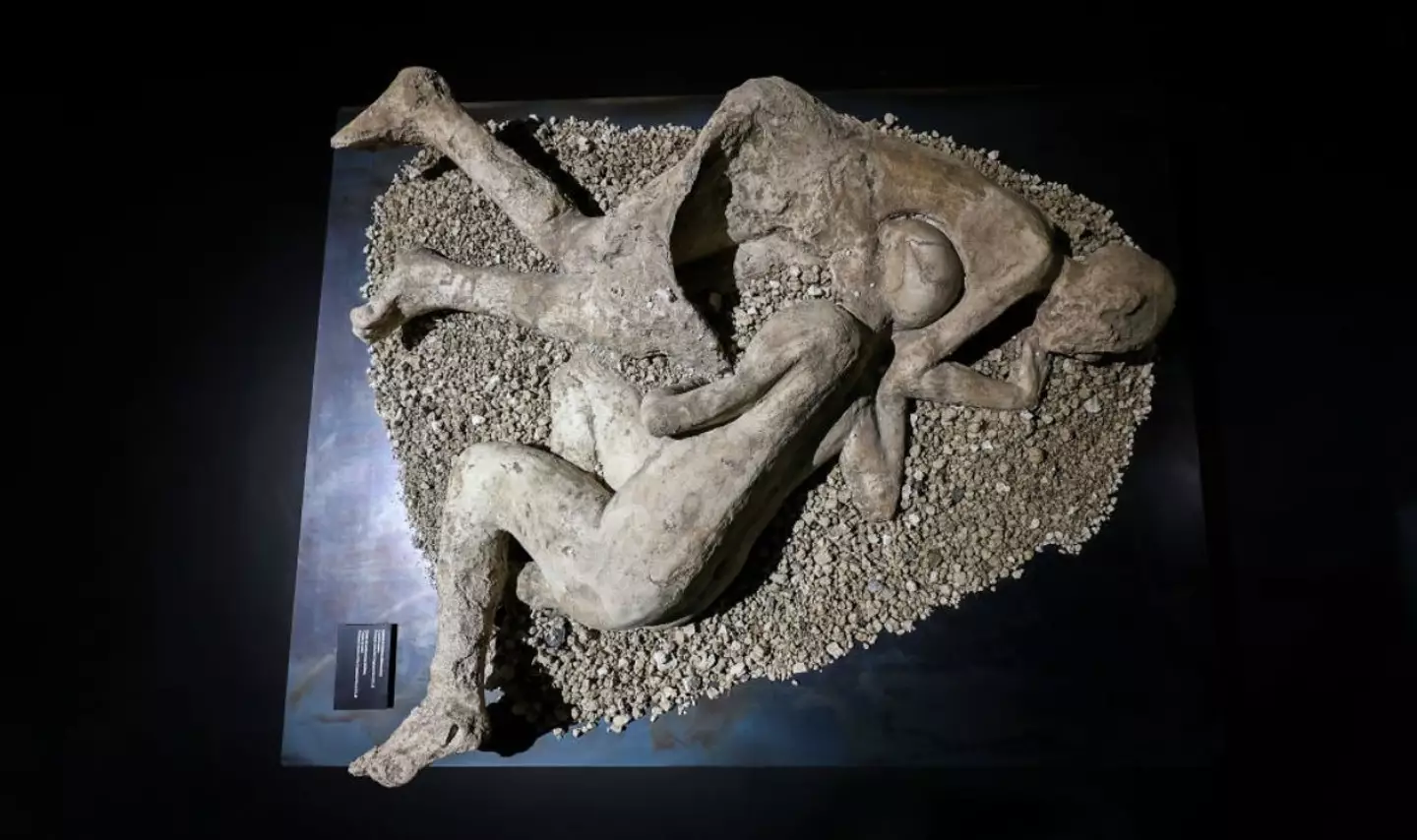

Excavations first began to unearth Pompeii in the 1740s, but it wasn’t until the 1860s that archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli began to make plaster casts of some of the victims whose bodies had been preserved by a thick layer of ash.

CNN reports that Italian expert Fiorelli preserved the shapes of 104 people by pouring plaster into the outlines left behind by decaying bodies.

Since then, various narratives and folklore regarding the Pompeians have made their way into the mainstream.

These include suspicions that a pair of individuals found together were thought to be sisters, and that an adult wearing a golden bracelet and holding a child was a mother-and-child duo.

.jpg)

Narratives surrounding the Pompeii casts have been dispelled (Getty Images)

But these family bonds are reportedly fiction, according to a new study published in the popular Current Biology journal.

In a bid to determine the victims gender, ancestry and genetic relationships, researchers from Italy’s University of Florence, the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig and Harvard University have been analyzing the ancient DNA of various casts.

On Thursday (November 7), the team published the results of their work, claiming that the cast of a woman who was holding the child was actually a genetic male

The DNA results also reportedly confirmed that the man was not actually related to the child he was holding.

Researchers have also determined that at least one of the presumed sisters found locked in an embrace was genetically male.

“This research shows how genetic analysis can significantly add to the stories constructed from archaeological data,” says Professor David Caramelli, from the Department of Anthropology at the University of Florence.

Ancient DNA has been analyzed by top researchers (Marco Cantile/LightRocket via Getty Images)

“The findings challenge enduring notions such as the association of jewellery with femininity or the interpretation of physical proximity as evidence of familial relationships.”

Another of the study’s authors, Professor David Reich, said: “The genetic results encourage reflection on the dangers of making up stories about gender and family relationships in past societies based on present-day expectations.”

“The scientific data we provide do not always align with common assumptions,” he continued. “For instance, one notable example is the discovery that an adult wearing a golden bracelet and holding a child, traditionally interpreted as a mother and child, were an unrelated adult male and child.

“Similarly, a pair of individuals thought to be sisters, or mother and daughter, were found to include at least one genetic male. These findings challenge traditional gender and familial assumptions.”

The study, titled ‘Ancient DNA challenges prevailing interpretations of the Pompeii plaster casts’, also states that many of the Pompeians who were killed when Mount Vesuvius erupted had diverse backgrounds.

.jpg)

Research has found the Pompeians killed in the eruptions had diverse backgrounds (Salvatore Laporta/KONTROLAB /LightRocket via Getty Images)

Their ancestry has predominantly been traced back to eastern Mediterranean immigrants, ‘underscoring the cosmopolitanism of the Roman Empire in this period’, as per the study.

“Our findings have significant implications for the interpretation of archaeological data and the understanding of ancient societies,” added Alissa Mittnik of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

“They highlight the importance of integrating genetic data with archaeological and historical information to avoid misinterpretations based on modern assumptions.

“This study also underscores the diverse and cosmopolitan nature of Pompeii’s population, reflecting broader patterns of mobility and cultural exchange in the Roman Empire.”

You can read the full ‘Ancient DNA challenges prevailing interpretations of the Pompeii plaster casts’ study, published via Current Biology here.